Mount Pleasant (Baltimore) 34/39 Deacon Care Family Ministry

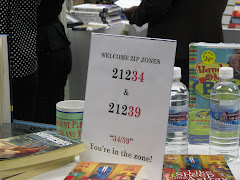

Welcome to the online home of the Deacon Care Family Ministry for the 21234 and 21239 zip codes of Mount Pleasant Church and Ministries, Baltimore, Maryland. We are better known as the "34/39 Zip Zone!"

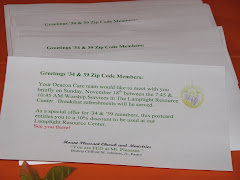

The Mount Pleasant members of 21234 and 21239 have joined together for a number of activities. Sunday breakfast at church, a Saturday breakfast and walk in the park, Sunday dinner, Meet and Greet after service, and a Resource Center Fellowship. Page down for the latest information, then enjoy the photo slideshow at the bottom of the page.

Blog Posts & Messages

Our blog posts begin here. We add both announcements and notices that are specific to 34/39 members and to Mount Pleasant's members at large. We try to update this site several times each month. We welcome your posts in the comment sections.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

FROM THE BALTIMORE SUN newspaper:

Families discuss 'living wage'

Can people live on the hourly rate? Here’s how some area residents are scraping by and raising families

By Jamie Smith Hopkins

Sun reporter

Originally published May 6, 2007

In all the wrangling, negotiating and back-patting, one point seemed overlooked when the 2007 General Assembly mandated that Baltimore-area government contractors pay their employees a "living wage" of $11.30 an hour.

Can someone actually live on that?

Barely, says Sandy Johns Jr., who just moved up from $11 to $12 an hour and is therefore more qualified than most to weigh in. He takes in just shy of $25,000 a year to cover expenses for himself, his wife and two young sons. The family sticks to a rigid budget. But if they weren't staying with his parents for reduced rent until Johns - an apprentice electrician - climbs higher on the salary scale, he doubts they could make it work.

"I'd probably have to look for a second job, something in the evening to make ends meet," said Johns, 30, who already spends two nights a week in apprenticeship classes.

Maryland's living-wage law, which goes into effect this fall, is the first in the nation to apply statewide, though many municipalities, including Baltimore, have them. An earlier attempt to enact a statewide standard was opposed by major business groups and vetoed by then-Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. in 2004.

The wage is two-tiered: $11.30 an hour for most of the Baltimore-Washington corridor and $8.50 for the rest of the state, to assuage concerns about the impact on rural jobs. Legislators settled on $11.30 because it would make many families ineligible for food stamps.

"We need jobs that allow people to access the middle class," said Del. Thomas Hucker of Montgomery County, a Democrat who campaigned for living-wage laws while he was executive director of Progressive Maryland, a "working families" advocacy group.

But sole providers earning the equivalent of the living wage are living so close to the edge that many qualify for other government help: Earned Income Tax Credit. Children's health benefits. Women, Infants and Children food vouchers. Even partially subsidized housing - though the waiting lists in the Baltimore area are so long that being eligible doesn't mean very much. Nearly 10,000 households are queued up for housing vouchers in Baltimore County alone.

Nonprofits that help people in trouble, such as hunger-relief groups and the Fuel Fund of Maryland, are used to seeing residents with hourly wages in the $11-to-$12 range. They're embarrassed to ask for help, said Mary Ellen Vanni, the Fuel Fund's executive director: "They feel like they should be able to pay their bills."

But even people earning more are falling behind as essential costs - rent, utilities, gasoline - have risen sharply. Housing is a key part of the problem. The National Low Income Housing Coalition calculates that a worker in the metro area would need to earn $18 an hour to rent an average two-bedroom apartment without spending more than 30 percent of his or her income. An efficiency would take $13.35 an hour.

Though the average Baltimore-area job pays $21 an hour, a variety of occupations pay less than the wage needed for an efficiency unit, such as school bus driver and bank teller. People cope by doubling up with relatives, making do with substandard housing, funneling large portions of their paychecks toward rent or taking second - even third - jobs.

The Human Services Programs of Carroll County, a nonprofit community action agency, said a recent client faced eviction and homelessness because her $950-a-month rent was too high for her $12-an-hour wage. She had lost the part-time job that had made up the difference.

"Every day we probably deal with five or six people or households that are facing some kind of similar situation," making around the living wage but unable to afford "very basic needs," said Stephen Mood, executive director of the Carroll group.

Workers earning close to $11.30 say balancing the budget is a constant concern.

"It's not easy," said Kenneth Pierson, 45, with a rueful laugh. He loves his job as a community outreach worker for the city Health Department, but the $12-an-hour wage isn't enough. "I have to carefully plan what I do."

Pierson drives a 12-year-old Lincoln and rents space in his parents' house, cutting his housing costs in half. He has no child care costs because his mother watches his 9-year-old daughter when she's out of school.

Even so, to cover his bills, he delivers pizzas three days a week on top of his full-time job. He figures you need to make at least $15 an hour to afford to live in the area, but $15-an-hour jobs appear few and far between. Most are either under or over.

"It seems like there's a divide," he said. "You get a job, it seems like you're making a lot or you're not making much of anything."

The way the state could help people earn family-supporting wages, he believes, is to pump more money into higher education. Pierson is making plans to study drafting and design at Baltimore City Community College, and that would be yet another bill to worry about if he didn't have scholarship money from a job with AmeriCorps a few years ago.

A variety of Baltimore residents are going to school in the hopes of a better-paying future. Archie Lee Sr., 50, a father of six earning $10.25 as an office clerk, is studying for a bachelor's degree. He dreams of turning his volunteer work in ex-offender counseling into a business.

His wife, Lakeisha, earns several thousand dollars a year, putting them just above the living-wage mark. But "things are very, very tight," said Lee, whose children range in age from 9 months to 11 years.

A critical part of their budget: $500 or so a month in food stamps, which they're eligible for because of the size of their household. "Without that, I don't know how we'd get by," he said. To avoid spending more than that allotment, they cook up two big meals a week - goulash, stews of beans and meat, spaghetti - and make each last for several dinners, he said.

A year ago they found a four-bedroom rowhouse for $700 a month; the city neighborhood has "some drug activity" but is mostly quiet, Lee said. They saved and saved to move from an apartment complex. Transportation is the "Batmobile," a 14-year-old van with space for the whole family that so far is still running.

A debt consolidation firm helps them spread out their bills. Entertainment, for the most part, is playgrounds, television, church. Sometimes they get loans from relatives, but he'd rather not.

"I talk with a lot of people, how they struggle, and all we can do is just pray for one another," Lee said. "I feel for people making minimum wages. I don't see how they get by, I really don't."

Leona Foster, 25, a data-entry supervisor who was making $12 an hour until a recent promotion pushed her to $15, is in training as a medical office assistant with plans to become a nurse. In the meantime, though, the only way to get by is to set priorities. For Foster, mother of a 4-year-old and a 7-year-old, it goes like this: Rent ($789 a month). Then food ($100 every other week, if she's lucky). Then everything else.

She's grateful she can get help from her mother when medical emergencies occur; her daughter has seizures, her son, asthma. While earning $12 an hour, Foster scrimped to put aside about $120 a month. She's hoping her new raise will make a difference.

"You feel as though you want to give up, but you can't," she said.

Still, $11.30 an hour sounds good to Jamila Mozeb, 26, whose pay dropped from $11.10 to $9.50 when her temp-agency job with Johns Hopkins Hospital turned permanent in February and she began getting Hopkins benefits. The mother of four is having to "rotate bills" - make partial or late payments. Sometimes she cooks up a big pot of spaghetti and calls it dinner for the week.

She realizes she's eligible for government help, but to get it she'd have to take a day off work, maybe two.

"If the BGE and gas wasn't so high, it would probably be a lot easier," said Mozeb, whose Baltimore Gas & Electric Co. bill alone is $200 a month.

For Sandy and Jasmine Johns, the trick to living on his $12 an hour is a combination of smart budgeting and family help. Sandy, the apprentice electrician, brings home $335 a week after deductions. His wife makes it stretch.

On a recent evening, the family piled into their recently paid-off Chevy Cavalier and headed for Giant Food in Towson, convenient to the neatly kept neighborhood of Northeast Baltimore rowhouses where they live with Sandy's parents and brother.

Sandy clutched the shopping list, Jasmine following with 5-year-old Alexander and 3-year-old Josiah. Into the cart went eggs, tuna fish and other items for breakfast and lunch, carefully chosen by Jasmine based on sales. ("No, I said Blue Ribbon whole grain white bread, two for $4," she said as Sandy mistakenly reached for Wonder Bread, which wasn't on sale.)

Sandy's parents shop for many of the costly dinner items. But Jasmine still has to forgo things she'd like - more expensive but healthier multigrain bread, for instance - to keep the weekly grocery run at $40, tops.

The grand total that day: $39.16. Almost everything they bought was on sale. (She made an exception for one spur-of-the-moment buy because the $1 Giant scratch-off ticket was a charity fundraiser.)

"She says, 'Don't exceed $40'; I say, 'Yes, ma'am,' " Sandy declared as they left.

Jasmine doesn't want to get further into debt. Roughly $20,000 in student loans hang over them from Sandy's days at Morgan State University. Though they negotiated a year's break, they'll see that $114-a-month bill again soon.

She knows it should get easier with time. Sandy is due for raises during his four-year apprenticeship; his earnings will continue to increase afterward. Once both boys are in school, Jasmine is hoping to start a catering business.

The thought of that future is the saving grace of making the budget work now, on $12 an hour.

"It's really not enough," said Jasmine, standing in the living room as her husband chatted with her father-in-law. "It's just not enough for someone who has a family, a wife and two kids. But also we're thankful. It's a good opportunity; he's doing something he loves. Eventually, we'll be there."

Post a Comment